Un autre écran

For a Free Palestine:

Films by

Palestinian Women

한국어 자막 지원 예정 * Tradução a caminho * Sottotitoli ITA a breve * Subtítulos en español disponibles en breve * 日本語字幕も作成中です* Subtitel Indonesia segera tersedia dalam waktu dekat

Available worldwide, with subtitles in multiple languages, from 18 May for a month.

New films will be added continuously.

Current line-up of filmmakers.

Already online: Jumana Manna, Basma Alsharif, Rosalind Nashashibi, Razan AlSalah, Mahasen Nasser-Eldin, Larissa Sansour, Mona Benyamin, Layaly Badr, Shuruq Harb.

Coming in the next couple of days: Emily Jacir, Lokman Slim/Monika Borgmann, Pary El-Qalqili, Mai Masri, Aida Ka'adan.

Donations go to facilitating medical, legal, and infrastructure aid on the ground. Secondary donations go to as supporting filmmaking in Gaza; restoration projects of older Palestinian films; cultural centres for refugees in the Occupied Palestinian Territories & more.

Programmed by Daniella Shreir.

With invaluable help, support, wisdom, knowledge and guidance from Missouri Williams, Yasmine Seale, Samia Labidi, Emily Jacir, Mona Benyamin, Charlotte Proctor and Frank Beauvais.

Translations into Arabic thanks to Yasmine Zohdi, Yasmine Seale, May Al Otaibi and Carine Chelhot Lemyre ; video editing help from Chrystel Oloukoï.

Web design: Daniella Shreir

متاح في جميع انحاء العالم، مع ترجمة بلغات متعددة، من ١٨ مايو لمدة شهر (لا تزال بعض أجزاء الموقع قيد الترجمة إلى اللغة العربية)

سيتم استخدام التبرعات لتسهيل المساعدة الطبية والقانونية والبنية التحتية في الميدان.

سيتم استخدام التبرعات الثانوية لدعم صناعة الأفلام في غزة ، ترميم الأفلام الفلسطينية القديمة ، دعم المراكز الثقافية للاجئين في الأراضي الفلسطينية المحتلة ، وأكثر من ذلك.

البرنامج برعاية دانيلا شرير بمساعدة ودعم وكرم وحكمة ومعرفة ميسوري ويليامز، ياسمين سيل، سامية لبيدي، اميلي جاسر، منى بنيامين، و فرانك بوفي

ترجمات الى العربية بفضل ياسمين زهدي، ياسمين سيل، مي العتيبي، كارين شلحوت لمير

Reem Shilleh

Perpetual Recurrences (An Exercise in Film Programming) (2016)

Layaly Badr

The Road to Palestine (1985, 7’)

ST: FR, ITA, KO, ES, PT (more languages to come)

Razan AlSalah

Your Father Was Born A 100 Years Old, And So Was The Nakba (2017, 7’)

ST: ES, FR, ITA, KO, PT (more languages to come);

Canada Park (2020)

Jumana Manna

Blessed Blessed Oblivion (2010, 21');

A Sketch of Manners (2013, 12') ST: FR, ES, PT (more languages to come);

A Magical Substance Flows into Me (2015, 67') ST: FR, ES, PT (more languages to come)

Mahasen Nasser-Eldin

The Silent Protest: Jerusalem 1929 (2019, 20')

Basma Alsharif

We Began By Measuring Distance (2009, 19’); Farther Than The Eye Can See (2012, 13’);

Home Movies Gaza (2013, 25'); O, Persecuted (2014, 12’)

Rosalind Nashashibi

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002, 7'); Hreash House (2004, 20');

Electrical Gaza (2015, 17')

Larissa Sansour

A Space Exodus (2009, 5’); ST KO, JP, PT (more languages to come)

Nation Estate (2012, 9’);

In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2016, 29’); ST FR (more languages to come)

In Vitro (2019, 28') ST: KO, FR (more languages to come)

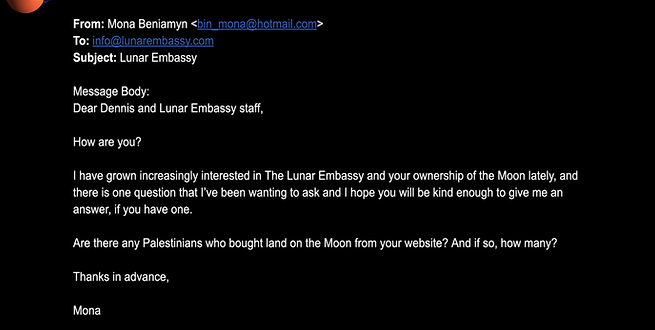

Mona Benyamin

Moonscape (2020, 17')

ST FR, PT, JP, KO, ITA (more languages to come)

Shuruq Harb

The White Elephant (2018, 12')

ST ES, FR, PT, JP (more to come)

Ahlam Shibli

Nine Days In Wahat al-Salam (2010)

Aida Ka'adan

Strawberry (2017)

Emily Jacir

Tal al Zaatar (1977 / 2014)

Focus on Mai Masri

Hanan Ashrawi: Woman of her Time (1995)

Children of Shatila (1998)

Frontiers of Dreams and Fears (2001)

Women Beyond Borders (2004)

33 Days (2007)

3000 Nights (2015)

COMING SOON:

Heiny Srour

The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived (1974)

Lokman Slim/Monika Borgmann

Massacre (2005)

When Things Occur (2017, 28')

When Things Occur is based on Skype conversations with Gazans that were behind images that were transmitted from screen to screen in the 2014 Israeli Onslaught on Gaza. The film probes the face of mourning and grief—its digital embodiment, transmission, and representation. It asks how the gaze gets channelled digitally, and how empathy travels. What exactly is viewing suffering ‘at a distance’? Who is ‘local’ in the representation of war? And what is the behaviour and political economy of the image of war?

Extract from: 'Toward a More Navigable Field' by Oraib Toukan

Palestinian self-representations seemed to recognize the power and speed of the reproduction of images from very early on. This is evident in the photographs by Sulafah Jadallah and Hani Jawharieh of Palestinian refugees-turned-resistance-fighters in the 1960s; in Mustafah Abu Ali, Khadijeh Habashneh, and the Palestine Cinema Institute’s transnational network of films in the 1970s; in Sliman Mansour and Ismail Shammout’s paintings reproduced into posters, calendars, and book covers across the Arab World in the 1980s; and among many others.1 The years of the Palestinian revolution (1968–82) not only represent the heyday of international and student activism for and within Palestine,2 inter-revolutionary friendship films, and politico-aesthetic battles between Marxist-Leninist movements.3 They were also an overall moment of total faith in the power of the silver halide compound to name a struggle.

Every new image of Palestine may begin to appear “something-like,” though not quite, but rather “similar-to” the last addition to an inventory—now a pile—of “Palestinian Images.”4 And for every image that’s been created, a chain of image-fragments can potentially be found in many bits, on many hard drives all over the world.5 “It’s a very crowded place,” wrote Edward Said in 1986, regarding the space of representations of Palestine, “almost too crowded for what it is asked to bear by way of history or interpretation of history.”6 In fact, Said impeccably referred to Palestinians as “the image that will not go away”:

To the Israelis, whose incomparable military and political power dominates us, we are the periphery, the image that will not go away. Every assertion of our non-existence, every attempt to spirit us away, every new effort to prove that we were never really there, simply raises the question of why so much denial of, and such energy expended on, what was not there?7

This “pile” of “Palestinian Images,” which was propelled by collective Palestinian consciousness to devictimize the image of the refugee, was eventually replenished by cruel images dehumanizing the Palestinian into someone who is “telegenically dead.”8 In an essay on the 2014 war on Gaza, Sherene Seikaly proposed that Palestine is itself as archive: an archive and “the archiving of moments of destruction and uprising, death and life, of loss and accumulation.”9 Seikaly’s writing conjures a flow of repeating and continually reappearing images of colonization and decolonization in the Palestinian time-space since the 1930s. These are images that Ariella Azoulay has also instrumentally slowed down in order to advocate for the individual civil claims that these photographs actually contain—revealing a civil language of photography itself, one that begins to more valuably find the perpetrator that photographs of suffering so often conceal.10

But rather than crying out, pictures that emanate from Palestine increasingly point to a question: “What exactly can’t you see in what I am seeing?” (or, put another way: What the fuck can’t you see in this?).The Palestinian story is as much a story of decolonization, civil strife, and massive injustice as it is about how best to show an injustice that feels like it cannot be seen. And so here lies a quandary: a disjunction between what feels like overrepresentation of the Palestinian subject, and a genuine frustration with an inability to see that subject. A dark, nondescript woman keeps reappearing on our screens. She is holding her chest in pain over some extreme loss, and is somewhere under siege in Gaza, occupied in the West Bank, obscured inside Israel, or exiled in a refugee camp in Lebanon, Syria, or Jordan.11 The original Sontagian claim that “too many” images of suffering anesthetize viewership can help explain this paradox of being represented while also not being seen, but this assertion has been exhausted, and is in any case a theoretical dead end. The problem persists, no matter how many cruel images12 have been scrolled over: Palestinians have remained a people in struggle no matter how many systems of separation have been created to dissolve that struggle.

Journal #101, June 2019, eflux

Read the rest here: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/101/272916/toward-a-more-navigable-field/

Oraib Toukan

Oraib Toukan is an artist primarily working in text, film, and photography. She is currently based in Berlin as an SNF fellow affiliated with EUME at the Forum Transregionale Studien. Until fall 2015, she was head of the Arts Division and Media Studies program at Al-Quds Bard College, Palestine, and visiting faculty at the International Academy of Fine Arts, Ramallah. Toukan received a BFA in Environmental Geography, followed by an MFA in Photography (2009) and a PhD in Fine Arts from the University of Oxford (2019), on the object and subject of Cruel Images. She is author of the book Sundry Modernism on Palestinian Modernism (Sternberg Press, 2017).

Perpetual Recurrences (An Exercise in Film Programming) (2016)

Reem Shilleh

ريم الشلة

التكرارات الدائمة، ٢٠١٦

Perpetual Recurrences is an exercise in programming films. Rather than curating a selection of entire films, this exercise curates a selection of scenes. Though they are montaged, the core of the exercise is to look at recurring patterns in Palestinian cinema and cinema on Palestine. The selected scenes gather around each other to form sequences. They do this dictated by repetitive occurrences be that location, political discourse, mise-en-scene, object and so on. From the classroom, to the militant in an open field delivering a speech with a tree somewhere in sight, to handheld camera shots in tight alleyways of refugee camps, to traveling shots from inside cars moving through streets, checkpoints and landscape, the scenes are plucked out from their heavily politicised filmic contexts, form and content wise. When placed in sequences they are screened to observe the political canopy of the moving image produced in and about Palestine over the past decades. The past era.”

The fragments were extracted from a number of films and videos created over the last four decades about Palestine, tracking repetition in works from militant filmmaking during the Palestinian revolutionary period 1968-82, the post-Oslo period and the more contemporary films and videos. The following are the titles of the films and their authors from which the scenes of this programme were extracted: “Oppressed People Are Always Right” (Nils Vest, 1976, Denmark); “Al-Fatah” (Luigi Perelli, 1970, Italy); “L’Olivier” (Groupe Cinéma Vincennes, 1976, France); “Palestine – RAF” (Almut Hielscher, Manfred Vosz and Hans-Jürgen Weber, 1971, West Germany); “The Palestinians” (Johan van der Keuken, 1975, Netherlands); “Palestine RE: (Video Test)” (Mahdi Fleifel, 2011, Denmark); “The Long March Of Return” (Ugo Adilardi, Carlo Schelliono and Paolo Sornaga, 1970, Italy); “The Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War” (Masao Adachi and Koji Wakamatsu, 1971, Japan); “Palestine In The Eye” (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1977, PLO); “They Do Not Exist” (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1974, PLO); “Fertile Memory” (Michel Khleifi, 1980, Palestine, Belgium, West Germany, Netherlands); “Pasolini Pa* Palestine” (Ayreen Anastas, 2005, Palestine); “Home Movies Gaza” (Basma Alsharif, 2013, Palestine, France).

التكرارات الدائمة هو تمرين في برمجة الأفلام. فبدلاً من تنظيم مجموعة مختارة من الأفلام بأكملها ، يقوم هذا التمرين بعمل تقييمي لمجموعة مختارة من المشاهد. جوهر التمرين هو النظر إلى الأنماط المتكررة في السينما الفلسطينية والسينما عن فلسطين. تتجمع المشاهد المختارة حول بعضها لتشكل تسلسلات. ويحكم هذه العملية الظهور المتكرر ليثيمات مثل مواقع التصوير والخطاب السياسي، والتصميم المشهدي (mise-en-scène)...إلخ، ابتداءً من صف مدرسي، إلى فدائي في حقل مفتوح يلقي خطابًا وهناك شجرة في مكان ما في الأفق، إلى لقطات الكاميرا المحمولة (hand held camera shot) في الأزقة الضيقة لمخيمات اللاجئين وإلى لقطات متحركة (traveling shots) من داخل السيارة تجتاز الشوارع والحواجز الاحتلالية والمناظر الطبيعية، حيث يتم نزع المشاهد من سياقاتها السينمائية المُسيسة (شكلاً ومضموناً) و وضعها في تسلسلات، الهدف من عرض هذه المشاهد هو مراقبة الظُلة السياسية التي تشكلت فوق صناعة الصورة المتحركة من وعن فلسطين.

تم استخراج المقاطع من عدد من الأفلام وأعمال الفيديو التي أنتجت على مدى العقود الأربعة الماضية حول فلسطين، لتتبع التكرار في أعمال صناعة الأفلام النضالية الثورية خلال فترة الثورة الفلسطينية 1968-1982، وفترة ما بعد اتفاقية أوسلو، والأفلام وأعمال الفيديو الأكثر حداثة. فيما يلي عناوين الأفلام ومؤلفاتها/يها الذين استخرجت منهم مشاهد هذا البرنامج:

"الفتح" (لويجي بيريلّي، 1970، إيطاليا)؛

"مسيرة العودة الطويلة" (أوغو أديلاردي، كارلو سكيليونو وباولو سورناغا، 1970، إيطاليا)؛

"الجيش الأحمر/الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين: إعلان الحرب العالمية" (ماساو أداتشي وكوجي واكاماتسو، 1971، اليابان)؛

"فلسطين ر.ف.أ." (ألمت هيلشر ، مانفريد فوس وهانس يورغن ويبر، 1971، ألمانيا الغربية)؛

"ليس لهم وجود" (مصطفى أبو علي، 1974، منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية)؛

"المضطهدون دائماً على حق" (نيلز فيست، 1976، الدنمارك)؛

"الفلسطينيون" (يوهان فان دير كوكن، 1975، هولندا)؛

"شجرة الزيتون" (جماعة سينما فانسان، 1976، فرنسا)؛

"فلسطين في العين" (مؤسسة السينما الفلسطينية، 1977، منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية)؛

"الذاكرة الخصبة" (ميشيل خليفي، 1980، فلسطين، بلجيكا، ألمانيا الغربية، هولندا)؛

"بازوليني في فلسطين" (أيرين أناسطاس ، 2005 ، فلسطين)؛

"عن فلسطين (تجربة فيديو)" (مهدي فليفل، 2011، الدنمارك)؛

"أفلام منزلية غزة" (بسمة الشريف، 2013، فلسطين، فرنسا)

Reem Shilleh is researcher, curator, editor, and on occasion writer. She lives and works between Brussels and Ramallah. Reem Shilleh’s practice is informed by a long research project on militant and revolutionary image practices in and around liberation and emancipatory struggles, in particular Palestine, its diaspora, and solidarity network. She is a member and co-founder of Subversive Film, a research, curatorial and production collective.

ريم الشلة باحثة ، وقيّمة معارض، ومحررة، وكاتبة في بعض الأحيان. تعيش وتعمل بين بروكسل ورام الله. إن ممارسة ريم الفنية مستوحاة من بحث طويل الأمد حول صناعة الصورة السينمائية الثورية من وعن نضالات حركات تحريرية وتحرُرية، مع التركيز على فلسطين و شتاتها وشبكتها التضامنية. هي عضوة مؤسِسة و مشارِكة في تحريض للأفلام، وهي مجموعة بحثية وقيمية وإنتاجية

The Road to Palestine (1985, 7’)

Layaly Badr

ليالي بدر

الطريق الى فلسطين (١٩٨٥، ٧ دقائق)

16 mm. Produced by the PLO.

An animated short film for children. The film is based on the testimony of the girl Laila, who saw some planes while her mother was combing her hair. She looked up at the sky and shouted to her mother, “the planes are sending balloons”. In actual fact, they were thermal balloons, falling directly to their target.

The Void Project is currently restoring, with the support of London Palestine Film Festival, films by women filmmakers, that were produced by the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), during what became known as “Palestinian cinema revolutionary era” .

فيلم رسوم متحركة للأطفال. يتبع الفيلم فتاة صغيرة تدعى ليلى، والتي تلحظ بعض الطائرات في السماء بينما تمشط أمها شعرها. تنظر لأعلى في دهشة بينما تقول لأمها: "الطائرات تسقط بالونات!" ولكنها في واقع الأمر بالونات حارقة، في طريقها إلى إصابة الهدف.

تم ترميم الفيلم بواسطة The Void Project. يعمل المشروع حاليًا بالتعاون مع مهرجان لندن للسينما الفلسطينية على ترميم أفلام لعدد من المخرجات أنتجتها منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية أثناء الفترة التي أطلق عليها "ثورة السينما الفلسطينية".

Layaly Badr is a Jordanian with Palestinian roots. She started working as a children’s story writer, before studying film-making in Germany and screenwriting in the New York Film Academy. She has two published books: ‘Lobana Wal Qamar’ and ‘Nahr Wa Shajara’. Badr haswon several awards for her films and television work. Her films are distinguished musicals, combining live action with animation. Her short movie “The Way To Palestine” won The Golden Lorbeer from the German TV, the best complete piece of work for children at the Arab TV Festival in Tunisia, the Pioneer Prize at the Damascus TV festival, and received a Special Mention at the Isphahan Children Film Festival.

Badr was the head of ART Children's Channel, then moved into the cinema industry as a producer and distributor. She worked as a managing director in the two biggest networks in the Middle East: ART and Rotana. She has also worked as a consultant for two of Egyptian networks: Al Nahar and ON TV. Currently she works as a freelancer.

ليالي بدر فنانة وصانعة أفلام أردنية من أصول فلسطينية. بدأت مشوارها ككاتبة قصص أطفال قبل أن تدرس صناعة الأفلام في ألمانيا ثم كتابة السيناريو في أكاديمية نيويورك للأفلام. لها كتابان منشوران: "لبنى والقمر" و"نهر وشجرة"، كما حصلت أعمالها السينمائية والتلفزيونية على العديد من الجوائز. حاز فيلمها القصير "الطريق إلى فلسطين" على جائزة لوربير الذهبية من التلفزيون الألماني وجائزة أفضل عمل للأطفال في مهرجان التلفزيون العربي بتونس، بالإضافة إلى جائزة الريادة في مهرجان دمشق للتلفزيون وتكريم من مهرجان أصفهان لسينما الأطفال. رأست بدر قناة ART للأطفال قبل أن تتجه للعمل في مجال السينما كمنتجة وموزعة، حيث عملت كمديرة في عدد من أهم الشبكات التلفزيونية في الشرق الأوسط مثل ART وروتانا، كما عملت بعد ذلك كمستشارة في شبكتين مصريتين كبيرتين، وهما النهار وON TV

Your Father Was Born A 100 Years Old, And So Was The Nakba (2017, 7’)

Razan AlSalah

رزان الصلاح

١٠٠ سنة، زي النكبة (٢٠١٧، ٧ دقائق)

Razan is an interdisciplinary artist currently investigating the material aesthetics of the dis/appearance of places and people in colonial image worlds. By breaking these thresholds of vision, her films lead us into an elsewhere in which colonialism no longer makes sense. Her work has been experienced in community-based and international galleries and film festivals. She teaches at Concordia University in Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal.

رزان فنانة تبحث حاليًا في الجماليات المادية لظهور او عدم ظهور الأماكن والأشخاص فيعوالم الصورة الاستعمارية ، محطمة عتبات الرؤية هذه إلى أماكن أخرى هنا ، حيث لميعد الاستعمار منطقيًا. تمتاز أعمالها بالخبرة في المعارض المجتمعية والدوليةومهرجانات الأفلام. تدرس في جامعة كونكورديا

A ghostly voice echoes: the disembodied, imaginary voice of the filmmaker’s grandmother, a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon who was never able to return to her hometown. Her words haunt Google Street View images of Haifa, the only means she could have had of visiting her lost home. But 50 years after the “great catastrophe,” the streets are no longer recognizable. The old woman’s soul wanders in vain through cyberspace in search of her house, probably demolished after the Nakba, and for her son Ameen, imagined as a little boy from another time. Over the images, which distort and pixilate as the network connection cuts in and out, are superimposed images of the trauma of forced relocation. Razan AlSalah pays heartbreaking tribute to the first generation of refugees. (Charlotte Selb, RIDM)

صدى صوت شاحب، بلا جسد: صوت من الخيال، هو صوت جدة المخرجة، لاجئة فلسطينية في لبنان لم تتمكن أبدًا من العودة إلى وطنها. يسكن صوتها صور من برنامج عرض شوارع جوجل (Google Street View) لمدينة حيفا، الوسيلة الوحيدة التي تستطيع بها زيارة بلدتها المفقودة. ولكن بعد مرور نصف قرن على النكبة، لم يعد بالإمكان التعرف على الشوارع. تهيم روح العجوز بلا فائدة عبر ذلك الفضاء الافتراضي بحثًا عن بيتها، والذي تم هدمه على الأغلب، وعن ابنها أمين، الذي تتصوره طفلًا صغيرًا من زمن بعيد. تركب فوق الصور -التي تهتز وتتشوّه وتـُ"بكسِل" مع انقطاع اتصال الإنترنت وعودته- صور أخرى لصدمة الإزاحة والتهجير القصري. تقدم رزان الصالح في هذا الفيلم تحية إجلال موجعة للجيل الأول من اللاجئين. (شارلوت سلب، RIDM)

I walk on snow to fall onto the desert. I find myself on unceded indigenous territory in so called Canada, an exile unable to return to Palestine. I trespass the colonial border as a digital spectre floating through Ayalon-Canada Park, transplanted over three Palestinian villages razed by the Israeli Defense Forces in 1967.

Canada Park is an experimental video poem exploring the politics of dis/appearance of Palestine as narrativized, mapped and imaged in Google Streetview and early 20th century colonial landscape photography of the ‘Holy Land’, namely at the site of the village of Imwas which is theologically conflated with Emmaus, a village cited in the bible. Imwas is erased and Emmaus marked a religious touristic site in the park, a self-fulfilled scriptural and algorithmic prophecy.

The park is located between what is commonly known as No Man’s Land and Jerusalem. The film explores this absurd space of suspension to create a counter mythology of this place against the religious, geopolitical and capitalist forces that actuated their imaginings on Palestine, people and land by reinserting the few images documenting the March of Return to Latroun that took place on June 16, 2007. Imwas is not erased. It is buried underground, an undercommons, an elsewhere here, where colonialism no longer makes sense.

I wake up again, feet on the ground in so called Canada; another park, Iroquois Mohawk territory. I walk on snow to fall unto the desert.

سيآتي قريبا

Blessed Blessed Oblivion (2010, 21') - A Sketch of Manners (2013, 12') - A Magical Substance Flows into Me (2015, 67')

Jumana Manna

جمانة مناع

مُبارك مُبارك النسيان (٢٠١٠، ٢١ دقائق)، موجز العادات (٢٠١٣، ١٢ دقائق)، في إثر مادة سحرية (٢٠١٥، ١٧ دقاىق)

Blessed Blessed Oblivion weaves together a portrait of male thug culture in East Jerusalem, manifested in gyms, body shops and hair dressing parlours. Inspired by Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963), the video uses visual collage and the musical soundtrack as ironic commentary. At the same time psychologising and seduced by the characters, Manna finds herself in a double bind — a dilemma that resonates with the muddled desire that animates her protagonist as he drifts from abject rants to declamations of heroic poetry or unashamed self-praise

مُبارك مُبارك النسيان

٢١ دقيقة، ٢٠١٠

مُبارك مُبارك النسيان ينسج صورة للثقافة البلطجية والذكورية في القدس الشرقية، تتجلى هذه البلطجية في الصالات الرياضية وصالونات العناية الشخصية و تصفيف الشعر. مستوحًا من صعود العقرب لكينيث أنجر 1963، يستخدم الفيديو الكولاج والموسيقى التصويرية كتعليقات ساخرة. وفي الوقت نفسه و بإغواء وسيطرة من قبل الشخصيات

تجد منّاع نفسها في مأزق مزدوج - معضلة تتصادف مع الرغبة المشوشة التي تحفز بطل الفيديو أثناء انجرافه من العواطف الحادّة إلى إلقاء الشعر البطولي أو الثناء على نفسه دون خجل

Jumana Manna is a visual artist working primarily with film and sculpture. Her work explores how power is articulated through relationships, often focusing on the body, land and materiality in relation to colonial inheritances and histories of place. Jumana was raised in Jerusalem and lives in Berlin.

جمانة مناع فنانة بصرية تعمل بشكل أساسي في صناعة الأفلام والنحت. يستكشف عملها كيف يتم التعبير عن السلطة من خلال العلاقات ، وغالبًا ما تركز على الجسد والأرض والمادية فيما يتعلق بالميراث الاستعماري وتاريخ الاماكن. نشأت جمانة في القدس وتعيش في برلين

Alfred Roch, member of the Palestinian National League, is a politician with a bohemian panache. In 1942, at the height of WWII, he throws what will turn out to be the last masquerade in Palestine. Inspired by an archival photograph, A Sketch of Manners (Alfred Roch’s Last Masquerade) recreates an unconventional bon vivant aspect of Palestinian urban life before 1948. Posing silently for a group photo, the unmasked and melancholic pierrots accidentally personify the premonition of an uncertain future.

موجز العادات (تنكريّة ألفريد روك الأخيرة)

نص مشترك مع نورمان كلين، ٢٠١٣، ١٢ دقيقة

صورة بالأبيض والأسود تم إلتقاطها عام ١٩٢٤ في حفل تنكري سنوي استضافه السياسي وعضو المجتمع الفلسطيني البارز،ألفريد روك ألهم عمل ملخص العادات. وقعت الصورة بيد مناع التي فُتنت بالحس المسرحي والتعامل الساخر مع الذات من خلال تصوير للحظة من لحظات الطبقة العليا في فلسطين قبل النكبة عام ١٩٤٨ بشكل مربك وغامض. يقوم"موجز العادات" بإعادة تمثيل هذه اللحظة بدعوة الأصدقاء والمعارف والأسرة من في جميع أنحاء فلسطين لحفلة تهريجية في فندق American Colony Hotel في القدس وهو موقع شهير وعلامة تاريخية للاستعمار في أوائل القرن العشرين. تم مونتاج اللقطات من هذه الحفلة مع صوت لنص تمت كتابته بالتعاون مع المؤرخ الثقافي نورمان م. كلاين. يروي الفيلم قصة شبه خيالية عن روك ومشاركيه في الحفلة: نظرة إلى عالم النخب الفلسطينية تحت الانتداب البريطاني. أثناء نقل الحدث من عام ١٩٢٤ إلى عام ١٩٤٢، "موجز العادات" يقوم بإعادة تحديد موقع فلسطين في تاريخ الأزمات العالمية وعواقبها مما يجعل آخر حفلة تنكرية لألفريد روك تعبيرً مسكون بهاجس السنين الصعبة التي تنتظرنا. ممثلون معاصرون يمثلون لحظة تاريخية ويبرزون البنية الطبقية والتناقضات في المشهد الثقافي لفلسطين، منذ ذلك الحين وحتـى اليوم

A magical substance flows into me opens with a crackly voice recording of Dr. Robert Lachmann, an enigmatic Jewish-German ethnomusicologist who emigrated to 1930s Palestine. While attempt- ing to establish an archive and department of Oriental Music at the Hebrew University, Lachmann created a radio program for the Palestine Broadcasting Service called “Oriental Music”, where he would invite members of local communities to perform their vernacular music. Over the course of the film I follow in Lachmann’s footsteps and visit Kurdish, Moroccan and Yemenite Jews, Samaritans, members of urban and rural Palestinian communities, Bedouins and Coptic Christians, as they exist today within the geographic space of historical Palestine. Manna engages them in conversation around their music, while lingering over that music’s history as well as its current, sometimes endangered state. Intercutting these encounters with musicians, are a series of vignettes of interactions of the artist with her parents in the bounds of their family home. In a metaphorical excavation of an endlessly contested history, the film’s preoccupations include: the complexities embedded in language, as well as desire and the aural set against the notion of impossibility. Within the hackneyed one-dimensional ideas about Palestine/Israel, this impossibility becomes itself a trope that defines the Palestinian landscape. –Negar Azimi

في إثر مادة سحرية

يبدأ الفيلم بصوت تسجيلي يعود لروبرت لاخمان، عالم موسيقي يهودي ألماني جاء إلى فلسطين في الثلاثينات في محاولة تأسيس أرشيف ودائرة للموسيقى الشرقية في الجامعة العبرية في القدس. وقد بادر لاخمان إلى برنامج إذاعي لهيئة إذاعة فلسطين أسماه "الموسيقى الشرقية"، دعا من خلاله أبناء المجتمعات المحلية لأداء موسيقاهم التراثية.

تتبع مناع خطى لاخمان وتقوم بزيارة أفراد مغاربة وأكراد ويهود يمنيون والطائفة السامرية، والفلسطينيين في الحضر والريف ومجتمعات البدو والمسيحيين الأقباط. كل منهم ينتمي لبيئات ثقافية مختلفة موجودة الآن في فلسطين التاريخية

The Silent Protest: Jerusalem 1929 (2019, 20')

Mahasen Nasser-Eldin

محاسن ناصر الدين

الإحتجاج الصامت (٢٠١٩، ٢٠ دقائق)

On 26 October 1929, Palestinian women launched their women’s movement. Approximately 300 women converged on Jerusalem from all over Palestine. They held a silent demonstration through a car convoy to protest the British High Commissioner’s bias against Arabs in the Buraq uprising. This is their story on that day.

المنتج/ة: ايميلي دودونيون

يعود بنا الفيلم إلى تاريخ 26 تشرين الأول/أكتوبر عام 1929، أي إلى اليوم الذي احتشدت فيه حوالي 200 امرأة فلسطينية في مدينة القدس، قادمةً من المدن والبلدات والقرى الكبرى في فلسطين من أجل تدشين حركتهنَّ النَّسويّة. «ننحتُ الكلمات في الأرض» هو رحلة في مشهد مدينة القُدس، تتبع خُطى النسّاء الفلسطينيّات اللواتي تنقَّلنَ بين ما يمثّل اليوم الجانبَين الغربي والشَّرقي للمدينة، إحتجاجاً على الحُكم الاستعماري البريطاني. بناءاً على السَّرديّات والجماليات السابقة واللاحقة للنَّكبة، يظهِرُ الفيلم الممارسات المناصرة لحقوق المرأة في فلسطين والترابط بين تجارب السياسية الماضية والحالية للنساء الفلسطينيات

Mahasen Nasser-Eldin is a Jerusalem born Director. Her films tell stories of resistance and resilience in pre and post-Nakba Palestine.

Mahasen graduated from Georgetown University in Washington D.C with a Masters in Arab Studies. She also holds a Master’s degree in filmmaking from Goldsmith’s College, London.

Mahasen currently teaches Film Production and Film Studies at the Dar al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture in Bethlehem.

محاسن ناصرالدين مخرجة أفلام وثائقية ومحاضرة جامعية من مواليد مدينة القدس. تروي من خلال افلامها قصص

وحكايات فئات واناس غيبهم الاهمال والنسيان وعانوا من الاقصاء والتهميش, اضافة الى توثيق تجارب وقصص انسانية

.تنطوي على معان سامية وعميقة وتجسد نموذجا استثنائيا في سياقها الاجتماعي والتاريخي

تهتم محاسن بالتاريخ الشفوي والتاريخ النسوي و تستند في افلامها الى الابحاث والنبش في ذاكرة التاريخ وذاكرة

الناس وتوظيف الارشيف المرئي والمسموع في اعادة بناء الرواية وتسليط الضوء على حيوات مهمشة ومنسية

عرضت افلامها في مهرجانات محلية وعالمية

Basma Alsharif

بسمة الشريف

We Began By Measuring Distance (2009, 19’), Farther Than The Eye Can See (2012, 13’) Home Movies Gaza (2013, 25'),

O, Persecuted (2014, 12’)

ابتدأنا بقياس المسافات (٢٠٠٩، ١٩ دقائق)، ابعد مما تراه العين (٢٠١٢، ١٣ دقائق)، اأفلام المنزلية غزة (٢٠١٣، ٢٥ دقائق)، يا إضطهاد (٢٠١٤، ١٢ دقائق)

Basma ALSHARIF is an Artist/Filmmaker of Palestinian origin, raised between France, the US and the Gaza Strip. She has a BFA and an MFA from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Basma developed her practice nomadically and works between cinema and installation, centering on the human condition in relation to shifting geopolitical landscapes and natural environments. Major exhibitions include: the Whitney Biennial, les Rencontres d'Arles, les Module at the Palais de Tokyo, Here and Elsewhere at the New Museum, Al Riwaq Biennial Palestine, The Berlin Documentary Forum, the Sharjah Biennial, and Manifesta 8. She was shortlisted for the Abraaj Group Art Prize, received a jury prize at the Sharjah Biennial 9 and was awarded the Marcelino Botin Visual Arts grant. Basma is represented by Galerie Imane Farés in Paris, distributed by Video Data Bank and Arsenal, and is now based in Berlin.

بسمة الشريف فنانة وصانعة أفلام من أصول فلسطينية. نشأت بين فرنسا والولايات المتحدة وقطاع غزة، وحصلت على شهادتي البكالوريوس والماجيستير من جامعة إلينوي بشيكاغو. طورت الشريف ممارستها الفنية بشكل متنقل، فتعمل بين السينما والتركيبات الفنية، وترتكز مشاريعها عادةً على الوضع الإنساني في تغيراته وعلاقته بالبيئة الطبيعية والظروف الجغرافية والسياسية المتحولة. من بين أهم المعارض التي شاركت فيها بأعمالها بينالي متحف الـ"ويتني" و"لقاءات أرلس" (Rencontres d’Arles) وLes Modules في قصر طوكيو بباريس ومعرض "هنا وهناك" (Here and Elsewhere) في "نيو ميوزيام" (New Museum) وبينالي الرواق بفلسطين وملتقى برلين الوثائقي وبينالي الشارقة ومانيفيستا ٨. وصلت إلى القائمة القصيرة لجائزة مجموعة أبراج الفنية وحصلت على جائزة لجنة التحكيم في بينالي الشارقة التاسع، كما حصلت على منحة مارسيلينو بوتين للفنون البصرية. يمثل الشريف غاليري إيمان فارس بباريس، كما يوزع أعمالها Video Data Bank و"أرسينال". تعمل وتعيش حاليًا في مدينة برلين.

A beholder waiting not to wait any more

By Eyal Sivan

“On December 31, 2013, at 9:25PM, Basma Alsharif wrote: I’ve been waiting (and waiting and waiting and waiting and waiting and waiting and waiting and waiting and waiting) for a permit to enter the PROMISED LAND.”

This sentence begins an email written from Amman by the visual artist and filmmaker Basma Alsharif, and it is neither a metaphor nor a quote. For the hundreds or thousands of Palestinians waiting before and after that last night at the end of the year 2013, “waiting for a permit” is neither a concept nor just ‘the reality,’ but rather an actual physical experience.

Born in Kuwait to Palestinian parents, raised and educated in France and in the US, travelling around the world armed with an American passport and working nomadically, Basma cannot (anymore) visit the country of her parents, the land where she would visit her grandparents as a child. Long before writing these ‘timeless Palestinian’ words, Basma’s body of visual works anticipates this present via a permanent exploration of the tension between the representation of reality and its physical experience. The encounter of the beholder with the filmic space unfolding along and through Basma’s work is corporeal. In this sense (and only in this one) watching Basma’s films and visual essays is a Palestinian experience.

While the great poet Mahmoud Darwish argued that “the metaphor of Palestine is stronger than the Palestine of reality”, Basma’s work makes the claim for a generation of young Palestinian internationalist artists that the Palestinian perspective is in fact stronger than the metaphor of Palestine. This notion of a Palestinian perspective, of a gaze steeped in History and splintered by geography, means refusing to be enslaved, refusing to be merely a support for projection but instead providing a critical reflection on the nature of this projection. Despite the administrative and social reminders of both the Palestinian being and the being-Palestinian, Basma privileges perspective in lieu of addressing explicitly what has come to be known as “the Palestinian question” or “the conflict.” Her vision goes beyond the ubiquitous symbolic and metaphoric reiteration of Reality. A fundamental component of the Palestinian (anti-colonial) struggle was, and in some regards, still is the struggle for a Palestinian image. It is the search for an image emancipated from its Orientalist and colonial representations and projections; a search for a genuine Palestinian representation of that space, its history, its people and their struggle. It is the search for a strict visual representation that rejects any possibility of confusion or misinterpretation. In Basma’s films, History and Space are represented through their multilayered and multi-linear dimensions. Images are seen through other images, frames collapse into other frames, space is familiar and anonymous, urban civilization and wildlife dissolve into each other as past, present and future collaborate on a single timeline. Basma is confronted both with a Neo-Orientalist social projection and with a self-Orientalist projection. This is why the emergency lies not in the struggle for the recognition of a Palestinian image but rather in the urgent interrogation of these social and political projections – in the urgent exploration of the nature of image, of representation itself. As such, Basma Alsharif’s work announces the arrival of what can be designated a post-Palestinian generation. In this way, she follows in Mahmoud Darwish’s claim: “I don’t decide to represent anything except myself – But this self is full of collective memory.”

Eyal Sivan for Galerie Image Farés

April 2014

ناظر ينتظر ألا ينتظر بعد الآن

A beholder waiting to not wait anymore

إيال سيفان

"في ٣١ ديسمبر ٢٠١٣، الساعة ٩:٢٥ مساءً، كتبت بسمة الشريف: لقد كنت أنتظر (وأنتظر وأنتظر وأنتظر وأنتظر وأنتظر وأنتظر) للحصول على تصريح لدخول الأرض الموعودة".

تبدأ هذه الجملة برسالة بريد إلكتروني كتبتها الفنانة البصرية والمخرجة بسمة الشريف من عمان، وهي ليست استعارة ولا اقتباس. بالنسبة لمئات أو آلاف الفلسطينيين الذين كانوا ينتظرون قبل وبعد الليلة الماضية في نهاية عام ٢٠١٣، فإن "انتظار تصريح" ليس مفهومًا ولا مجرد "واقع"، بل هو تجربة جسدية فعلية.

ولدت في الكويت لأبوين فلسطينيين، وترعرعت وتعلمت في فرنسا والولايات المتحدة، وسافرت حول العالم مسلحة بجواز سفر أمريكي وتعمل كالرحالة، ولم تعد بسمة قادرة (بعد الآن) على زيارة بلد والديها، الأرض التي كانت ستزور فيها جديها عندما كانت طفلة. قبل وقت طويل من كتابة هذه الكلمات "الفلسطينية الخالدة"، تتنبأ مجموعة أعمال بسمة المرئية بهذا الحاضر من خلال استكشاف دائم للتوتر بين تمثيل الواقع وتجربته الجسدية. إن لقاء الناظر مع المساحة السينمائية الذي يتكشف عبر عمل بسمة ومن خلاله هو لقاء جسدي. بهذا المعنى (وفقط في هذا) فإن مشاهدة أفلام بسمة ومقالاتها المرئية هي تجربة فلسطينية. على الرغم من التذكيرات الإدارية والاجتماعية لكل من الكائن الفلسطيني وأن تكون فلسطينيا، فإن بسمة تتمتع بالمنظور بدلاً من المعالجة الصريحة لما أصبح يُعرف باسم "القضية الفلسطينية" أو "الصراع". تتجاوز رؤيتها التكرار الرمزي والمجازي في كل مكان للواقع. كان أحد المكونات الأساسية للنضال الفلسطيني (ضد الاستعمار)، ولا يزال في بعض النواحي، النضال من أجل صورة فلسطينية. إنه البحث عن صورة متحررة من تصوراتها وإسقاطاتها الاستشراقية والاستعمارية. البحث عن تمثيل فلسطيني حقيقي لتلك المساحة وتاريخها وشعبها ونضالهم. إنه البحث عن تمثيل مرئي صارم يرفض أي احتمال للارتباك أو سوء التفسير. في أفلام بسمة، يتم تمثيل التاريخ والمساحة من خلال أبعادهما المتعددة الطبقات والمتعددة الخطوط. تُرى الصور من خلال صور أخرى، وتنهار الإطارات في إطارات أخرى، والمساحة مألوفة ومجهولة الهوية، والحضارة الحضرية والحياة البرية تتلاشى مع بعضها البعض حيث يتعاون الماضي والحاضر والمستقبل في جدول زمني واحد. تواجه بسمة كلا من الإسقاط الاجتماعي الاستشراقي الجديد وإسقاط الاستشراق الذاتي. لهذا السبب لا تكمن حالة الطوارئ في النضال من أجل الاعتراف بالصورة الفلسطينية بل في الاستجواب العاجل لهذه التوقعات الاجتماعية والسياسية - في الاستكشاف العاجل لطبيعة الصورة، والتمثيل نفسه. على هذا النحو، تعلن أعمال بسمة الشريف عن وصول ما يمكن تسميته بجيل ما بعد الجيل الفلسطيني. وبهذه الطريقة، تتبع ما قاله محمود درويش: "أنا لا أقرر أن أمثل أي شيء سوى نفسي - لكن هذه الذات مليئة بالذاكرة الجماعية"

إيال سيفان Galerie Image Farés

أبريل ٢٠١٤

Long still frames, text, language, and sound are weaved together to unfold the narrative of an anonymous group who fill their time by measuring distance. Innocent measurements transition into political ones, examining how image and sound communicate history. We Began by Measuring Distance explores an ultimate disenchantment with facts when the visual fails to communicate the tragic.

سيآتي قريبا

A woman recounts her story of the mass exodus of Palestinians from Jerusalem. Beginning with the arrival and ending with the departure, the tale moves backwards in time and through various landscapes. The events are neither undone nor is the story untold; instead, Farther than the eye can see traces a decaying experience to a place that no longer exists.

On 'Farther than the eye can see'

The center cannot hold. The whirling vortex of Basma Alsharif’s Farther than the eye can see provides a destabilizing and disorienting complement to Shimon Attie’s MetroPAL.IS., on view in the adjacent gallery. Attie’s installation places viewers in the center of a Roman senate of video monitors that provides unified and divergent readings of Israeli and Palestinian national and personal identities. Although viewers of that work are compelled to pivot and drift among the eight monitors surrounding them, they remain drawn to and comfortable within the center of the ellipse. Alsharif’s video, shown as a single projection, offers a more fixed presentation than Attie’s immersive installation, but it too draws out a physical response.

The video’s prologue sets the tone: after an opening gunshot, a synchronized voice and text play overtop of a swirling deep blue colorfield. This visceral combination of sound and image brings out a bodily response in viewers and, at the video’s densest moments, creates a sensation akin to centrifugal force. The sense of motion and perceptual disorientation can be so overwhelming and staggering that viewers feel a distinct pressure on their chests as the video propels them away from the screen. The Latin origins of the word centrifugal translate as “center fleeing,” an apt phrase on many levels. Attie’s installation draws viewers into the middle of the space and allows for multidirectional dialogues and exchanges; Alsharif’s exerts a strong, unified force that destabilizes and pushes the viewer away from any sense of “center.”

The story at the heart of Farther than the eye can see is a move away from a center. A woman recounts her birth in Jerusalem in 1938 and her family’s flight to Egypt a decade later when Israel was established as a state. But the tale is mediated in several ways. Overtop of the woman’s narration of her story, Alsharif layers a male voice retelling her story in English, but it’s a tale told at a remove and out of chronological order. The speaker structures the woman’s story in reverse, starting with the flight and ending with her birth. Effect and cause. Place out of time.

Throughout, one of the primary visual motifs Alsharif uses is a Janus-faced perspective shot. Initially, we get a shot of Alsharif riding her bicycle with the view in front of her superimposed with a rear view of the landscape beyond her. Then the video builds to a lengthy, frenetic sequence (during the woman’s recitation of her exile from Palestine to Egypt) that alternates between frontal and rear views of the Jerusalem skyline, creating an effect that recalls pre-cinematic thaumatropes. But instead of creating a joint third conjunction from the rapid juxtaposition of two distinct images, Alsharif’s rapid cycling of frames creates a point of view that simultaneously contains the past and the present.

In time-based art, viewers are most frequently confronted with the present moment. But in Farther than the eye can see, Alsharif finds ways to scramble our physical and mental responses so that they can never get settled into the moment at hand. A distance always has to be crossed. A conversion always has to be navigated. (These brief notes don’t have space for a detailed discussion of Alsharif’s masterly use of text and voice in the video.) This allows viewers to confront a nuanced articulation of one of the dominant concerns of Alsharif’s work: the subjective experience of statelessness. Farther than the eye can see uproots viewers. It makes them flee the center. The experiential condition that arises allows for a bodily understanding of the larger political and intellectual issues at play.

I’d recommend that you, the reader of this card, stick around and let the video play through again. That’s why we’re showing it on a continual loop all month. Stick around again for the part right after the title card. When the image cuts to black and there’s an intense refrain of clapping. Feel this moment inside yourself. This feels important. I don’t want to write about this moment for you. This moment is for you. Do you feel it? What is it? Why is it like this? What can we do? Will we do it? Do we dare? You go first. No really. You go first. I’ll be right there behind you. I think we can see the way. We just need to tie language back to our bodies. We just have to see farther than the eye can see.

Chris Stults

wexner center for the arts, 2013

بسمة الشريف

أبعد مما ترى العين (2012)

لا يستطيع المركز أن يصمد.

يمكن النظر إلى الدوامة الدائرة بالقلب من "أبعد مما ترى العين" لبسمة الشريف كمتممٍ مربك لعمل شيمون عطية المعنون .MetroPAL.IS والمعروض بالقاعة المجاورة. يضع التركيب الفني لعطية المتفرجين وسط مجموعة من الشاشات التي تعرض تصورات موحدة ومتفرقة في آن عن الهوية الشخصية الفلسطينية والإسرائيلية. رغم أن مشاهدي هذا العمل يشعرون برغبة ملحة في التنقل هائمين بين كل من الشاشات الثمانية المحيطة بهم، إلا أنهم يظلوا منجذبين إلى مركز الدائرة، يشعرون براحة أكبر هناك. يقدم فيديو الشريف، والذي يعرض على شاشة واحدة، صورة أكثر جمودًا عن تلك التي يمنحها تركيب عطية الذي يغمر المشاهد في تفاصيله، إلا أنه -هو أيضًا- يثير رد فعل عضوي في المتلقي.

تبدو نبرة الفيلم واضحة من مقدمة الفيديو: بعد طلقة افتتاحية، يظهر نص وصوت مترافقين على خلفية لونية زرقاء تدور وتدور باستمرار. يحفز هذا المزج بين الصوت والصورة استجابة بدنية في المُشاهد، كما يخلق -في أكثر لحظات الفيديو تكثيفًا- شعورًا يشبه قوة طرد مركزية. أحيانًا يكون هذا الشعور بالحركة الدائمة والارتباك البصري طاغيًا لدرجة تجعل المشاهد يشعر بضغط في صدره يدفعه بعيدًا عن الشاشة. الترجمة الحرفية للأصل اللاتيني لكلمة centrifuge -أي الطرد المركزي- هي "center fleeing"، أو الهروب من المركز، وهي عبارة دقيقة على أكثر من مستوى. يجذب التركيب الفني الخاص بعطية المشاهدين إلى مركز المساحة المعروض فيها، ويعطي مجالًا لحوارات وتبادلات متعددة الاتجاهات، بينما تنبع من فيديو الشريف طاقة قوية وموحّدة، تزعزع استقرار المتفرج وتبعده عن أي إمكانية للتمركز.

تعد قصة "أبعد مما ترى العين" هي ذاتها رحلة ابتعاد عن مركز معيّن. تحكي امرأة عن مولدها في القدس عام 1938 وهروب أسرتها إلى مصر بعد مرور عقد، عقب إعلان إسرائيل كدولة. إلا أن القصة تُسرَد بتدخلات عديدة؛ فالسرد هنا طبقات: فوق صوت المرأة التي تحكي قصتها، تسجل الشريف صوت رجل يحكي نفس القصة بالإنجليزية، ولكنه يحكيها من على مسافة ودون مراعاة للترتيب الزمني. يبني هذا الصوت الدخيل قصة المرأة من النهاية إلى البداية؛ يبدأ بهروبها وينتهي عند مولدها. النتيجة قبل السبب، والمكان بلا زمان.

أحد الموتيفات البصرية الأساسية التي تستخدمها الشريف طوال الفيديو هي لقطة من منظور مزدوج: نرى الشريف تقود دراجتها بينما تركب صورة المشهد الذي تركته وراءها على صورة للمشهد الذي مازال أمامها. ثم يقودنا الفيديو إلى متتالية طويلة ومحمومة (بينما تحكي المرأة قصة تهجيرها وأسرتها من فلسطين إلى مصر) تتكون من صور متنافرة لمدينة القدس، تاركة أثرًا يذكرنا بلعبة الأقراص المتقلبة (thaumatrope) السابقة لاختراع السينما. ولكن بدلًا من خلق صورة ثالثة إثر الدمج السريع لصورتين مختلفتين بوضوح، يصنع هذا التدوير الخاطف للكادرات وجهة نظر تحتوي الماضي والحاضر في الوقت ذاته.

في الأعمال الفنية المبنية على الزمن، عادة ما يواجَه المتفرج باللحظة الحالية. ولكن في "أبعد مما ترى العين"، تجد الشريف طرقًا لإرباك ردود أفعالنا العقلية والبدنية بشكل لا يسمح لنا بالاستقرار في الحاضر. هناك دومًا مسافة نحتاج لاجتيازها، تحول علينا استكشافه. (ليس هناك مجال في ملاحظاتي المختصرة هذه للاستفاضة في النقاش حول مهارة الشريف في استخدام النص والصوت داخل الفيديو). يمنح هذا الفرصة للمتفرج أن يواجه صياغة دقيقة ومتعددة الطبقات لأحد أكثر الهموم هيمنة على أعمال الشريف: التجربة الذاتية لحالة "اللاوطن". يقتلع "أبعد مما ترى العين" المتفرج من جذوره، يجعله يهرب من المركز. يسمح الظرف الشعوري الذي تتسبب فيه مشاهدة الفيديو للمتلقي أن يفهم -على المستوى العضوي والجسماني- القضايا السياسية والفكرية التي يطرحها العمل.

أوصيك أيها القارئ/أيتها القارئة بالبقاء ومشاهدة الفيديو مرة ثانية. لهذا نعرضه في تتابع مستمر لمدة شهر كامل. انتظر/ي الجزء الذي يأتي بعد التتر مباشرةً، حين تسودّ الشاشة ونسمع تصفيق حاد ومتتابع. اشعر/ي بهذه اللحظة في داخلك. شعور بأن شيئًا ما هامًا يحدث. لا أريد أن أكتب لك عن هذه اللحظة. هذه اللحظة لك أنت. هل تشعر/ين بها؟ ما هي؟ لماذا هي كذلك؟ ماذا بوسعنا أن نفعل؟ هل سنفعله؟ هل نجرؤ؟ أجب أنت أولًا، وسأتبعك. أعتقد أن بإمكاننا أن نرى الطريق الآن. علينا فقط أن نربط اللغة بأجسادنا مرة أخرى. علينا فقط أن ننظر أبعد مما ترى العين.

كريس ستلتس

المنسق المساعد للفيديو والأفلام

Home Movies Gaza introduces us to the Gaza Strip as a mircrocosm for the failure of civilization. In an attempt to describe the everyday of a place that struggles for the most basic of human rights, this video claims a perspective from within the domestic spaces of a territory that is complicated, derelict, and altogether impossible to separate from its political identity.

سيآتي قريبا

Home Movies Gaza Series: Regarding the Pain of Others

by Rasha Salti

Gaza is home to Basma Alsharif: it’s where her mother is from; where she has spent the summer vacations and holidays of her childhood and some in her adulthood. She also calls Chicago home, and perhaps a few years from now, Amman, or Beirut, or Los Angeles. She is that (first) generation of diaspora Palestinians who have learned to belong in a back and forth between cities in the north and south, east and west. As an adult, she has come to realize that she is in fact without a place of permanent residence, and has yet to strike roots of her own choosing. To make a place and call it home. She carries bonds to cities where she has lived, attachments real and consciously woven, emotional, psychological, cultural, somatic, complicated, paradoxical, at once precise and inchoate, differentiated and diffused. They articulate in emotional and poetic associations.

For the past few years, Alsharif has traveled as an artist in residency to Arab cities lacing the besieged Bantustan of Gaza: Amman, Beirut, Cairo… An artist in temporary residency with a suitcase of things, cameras and notebooks. In October of the past year, she decided to accompany her grandmother to her home in Gaza, journeying from Amman, via Cairo, to the Rafah border entry. Her grandmother had not been home in years, she had fled for safety under duress after the last major Israeli military campaign.

What is that mysteriously subjective interior universe we call home? And what if one’s home were in the Gaza Strip? In Home Movies Gaza, Alsharif’s camera wanders, filming the road to her grandparents’ home, streets and walls that besiege neighborhoods, etched with graffiti and slogans, nooks of the house, corners of her garden, the beach, a crackling radio broadcast, the sinister grumble of air drones. The most basic of everyday life’s seemingly mundane elements, except that they are set against the backdrop of the reality of the Gaza Strip. Like Soweto in the 1970s, Beirut in the 1980s, Sarajevo in the 1990s, in our present decade Gaza has become eponymous to a superlatively war-ravaged, tragedy-stricken place, at once detached from the temporality of the rest of humanity and the mirror of its heart of darkness. Representations of the Gaza Strip are scarce; firstly, they are almost exclusively camera footage and reportage broadcast by international news agencies – when the Israeli army allows it. Secondly, they usually mediate a heart-wrenching testament to the horrors inflicted on Gazans: we see blood-drenched bodies of women and children wailing for rescue, makeshift hospitals struggling to save lives, flattened buildings, the squalor of life reduced mercilessly to its barest elements, outrage and the politics of rage…

How to reconcile such violent superlatives with the intimate, tender and deeply subjective associations that we weave around a place called home? Basma Alsharif’s home videos are the digital filmic essays in which she explores these questions, where she attempts to parse, capture, stitch and share poetic vignettes that reconcile between such radically contrasted sentiments. Can one sing a lullaby against the sound of military drones grumbling in the sky? Carve the space-time to accept the pleasure of the morning against the tirelessly irrevocable threat of imminent military attack? People do, everyday Gazans have developed the ability to appease their babies with lullabies, knowing that at any moment, a shell might land in the middle of their house and destroy their lives again. They have not acquired these skills unscathed, something deep within is invariably lost, broken, perhaps beyond retrieval. Their knowledge of being in a world whose indifference affords their tormentors not only impunity, but self-righteousness. Alsharif’s convulsively placed home movies/videos interpellate that indifference and its mute gnawing on the consciousness of Gazans.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag’s widely acclaimed and last book before her passing, she proposed a bold meditation on the essential inability of (still) photography to mediate truly the experience of enduring violence, trauma and torture in times of war. Basma Alsharif’s series Home Movies Gaza suggest, humbly and tentatively, otherwise. Perhaps the generous sharing of her purely subjectively-constructed realms that make up her home, the intimation to her singularly poetic associations, the power of the moving image coupled with sound, transpose a more complex, emotional and psychological experience that not only lodges itself in the viewer’s consciousness, but surreptitiously resonates with one’s own subjective poetic associations of one’s home. It is not a process of identification, but of an unsuspected and uncanny recognition, that jettisons the poignant, unimaginable everyday reality of Gaza from the nether, far flung world of ‘exceptionalism’ into one’s here and now.

سيآتي قريبا

O, Persecuted turns the act of restoring Kassem Hawal’s 1974 Palestinian Militant film Our Small Houses into a performance possible only through film. One that involves speed, bodies, and the movement of the past into a future that collides ideology with escapism.

"Basma Alsharif’s O, Persecuted confronts layers of history and ideology emanating from a recently restored 1974 Palestinian militant film. The grainy black-and-white images often appear hidden, barely glowing from beneath a thick, perhaps painted surface, which a performer methodically removes over the course of the film... There is an outburst of energy as the film shifts registers and shows a series of wildly energetic beach party images. Alsharif diagnoses a troubling uncertainty and disengagement in youth which slingshots from the past to the present day." — James Hansen, Filmmaker Magazine

سيآتي قريبا

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002, 7') - Hreash House (2004, 20') - Electrical Gaza (2015, 17')

Rosalind Nashashibi

روزاليند نشاشيبي

In ‘Electrical Gaza’ Nashashibi combines her footage of Gaza, and the fixer, drivers and translator who accompanied her there, with animated scenes. She presents Gaza as a place from myth; isolated, suspended in time, difficult to access and highly charged.

في "كهرباء غزة" تدمج النشاشيبي مقاطع مصورة لغزة والمنسق المحلي والسائقين والمترجم الذين صاحبوها هناك مع مشاهد رسوم متحركة. تصوّر المخرجة غزة كمكان أسطوري، معزول ومعلّق في الزمن؛ مشحون بالمشاعر والتوترات ويصعب الوصول إليه

Rosalind Nashashibi is a London-based artist working in film and painting. Her films use both documentary and speculative languages, where real-life observations are merged with paintings, fictional or sci-fi elements to propose models of collective living. Her paintings likewise operate on another level of subjective experience, they frame arenas or pools of potential where people or animals may appear, often in their own context of signs and apparitions that signal their position for the artist.

Nashashibi has showed in Documenta 14, Manifesta 7, the Nordic Triennial, and Sharjah X, She was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2017 and won Beck’s Futures prize in 2003. She represented Scotland in the 52nd Venice Biennial. Most recent solo shows include Vienna Secession, CAAC Seville, Chicago Art Institute and Kunstinstuut Melly, Rotterdam. She was artist in residence at the National Gallery 2019-21 and is a senior lecturer at Goldsmiths.

روزاليند النشاشيبي فنانة مقيمة في لندن تعمل في مجال السينما والرسم. تستخدم أفلامها كلاً من اللغات الوثائقية والتأملية، حيث يتم دمج ملاحظات الحياة الواقعية مع اللوحات والعناصر الخيالية أو الخيال العلمي لاقتراح نماذج للحياة الجماعية. تعمل لوحاتها أيضًا على مستوى آخر من التجربة الذاتية ، فهي تخلق ساحات من الإمكانات حيث قد يظهر الأشخاص أوالحيوانات ، غالبًا في سياقها الخاص من الإشارات او المظاهر التي تشير إلى موقعهم للفنان.

ظهرت الفنانة في Documenta 14 ، Manifesta 7 ، The Nordic Triennial ، و Sharjah X . تم ترشيحها لجائزة تيرنر فيعام 2017 وفازت بجائزة بيك فيوتشرز في عام 2003. مثلت اسكتلندا في بينالي البندقية الثاني والخمسين. تشمل أحدثالعروض الفردية Vienna Secession ، CAAC Seville ، معهد شيكاغو للفنون و Kunstinstuut Melly ، روتردام. ايضاكانت فنانة مقيمة في المعرض الوطني ٢٠١٩-٢١ وهي محاضرة في Goldsmiths

NO DIALOGUE

DANIELLA SHREIR: Why do you leave your films unsubtitled?

ROSALIND NASHASHIBI: I thought that if I had subtitles, people would read it as text, and the meaning would be too closely associated with what people were saying, and it wasn’t really about that. Most of my films at that time were about how people navigate the institutions that they have, or that they inherit, or that they build. And so I didn’t really think it was important. Now I might have done it just to be generous and to give people the information they might want to know, but then that wasn’t on my mind.

DS: Why do you think there’s been that change? Like why is the idea of educating people something that’s more on your mind than it was six years ago?

RN: I’m not sure. I suppose that the identity politics around filming people has become so much more acute and specific, but back then for me not translating them was preserving their privacy. I thought it was a respectful thing to do. But now I think that people feel you’re taking away someone’s voice, which I never felt I was ever doing, because the voice is there. So people might say that you’re taking away someone’s voice, for example, if we can’t understand them, but there’s also the sense that what they mean is you’re not giving me the code, the way in, you’re not giving me access. But I wanted to show what I observed, and I didn’t know what they were talking about. I found out later only to be sure that if there was something important I could make a decision about their privacy – so I found out what they were saying but I didn’t translate it. In Electrical Gaza, people are saying things that I just thought were their business, not mine.

DS: No, absolutely. It’s also interesting whether or not the viewer knows that you are not an Arabic speaker yourself, because if one assumes that you are then it seems like a contract between you and the subject, which allows for a privacy that doesn’t allow for like another – I was going to say another gaze [laughs]… But the spectator who is not Arabic can’t understand and that is…

RN: Yeah, but it’s not deliberately shutting out.

DS: No, I think it’s the opposite. A lot of people talk about the politics of not subtitling in Indigenous films, for example, as a means of creating respect and privacy and not assuming that the white audience should have access to everything. It’s fascinating too you’re capturing your own experience. It conveys your own experience of not understanding even more strongly.

RN: Exactly. That’s what I tried to do in every single one of these films, to find a way to show for the viewer how it felt for me to be there. And in Gaza being there was so intense, and so charged – that’s why I called it Electrical Gaza – and so traumatic and dangerous, and yet exciting, wonderful and inclusive too. It was really dark, but also somehow really warm. So, that’s what I wanted to put across and that’s why in that film I used my breath – for the first time you hear me breathing, because I just thought I wanted to be more explicit about the fact that I was there and not just a fly on the wall, but a physical person.

Rosalind Nashashibi’s new film Electrical Gaza, 2015, recasts Gaza as an enchanted place behind sealed borders, codified through danger and division, bristling with beauty and life. Shot prior to the most recent Israeli assault on the area in 2014, it images scenes of the region where violence is, for once, not at the center. The camera luxuriates in quotidian life: Kids play in an alley, horses are washed in the searing blue Mediterranean, and men prepare falafel and sing together in a living room.

Every so often, Nashashibi’s footage morphs into computer-modeled animations resembling children’s stories. The music—uplifting synth—that frames certain scenes feels foreign to the context and calculatedly cloying. Fixed in these filters, brushed with a knowing sentimentality, Gaza seems an impossible fiction. Nashashibi’s films have a tendency to twist back on themselves, showing artifice by way of cinematic construction. Whereas in her other films, her slow, probing camera can inject magic into seemingly routine activities, in Electrical Gaza there is another force at work. These scenes are threatened by tragedy implicit to this region, which loops back upon questions of exoticization bound up in Nashashibi’s own gaze. One final shot pans across the Rafah sky looking toward Egypt, resting at the border crossing. Accompanying this scene is Benjamin Britten’s Fanfare (1939), an operatic adaption of Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations. Its words translate to “I alone hold the key to this savage parade.” But this work, if any, knows the falsity of this sentiment. — Alex Davidson for Frieze

الفيلم الجديد للمخرجة روزاليند نشاشيبي " الكتريكال غزة "، يعرف غزة بمكان ساحر خلف الحدود المغلقة، مقيدةً بالأخطار والانقسامات. ولكنها، وللمرة الأولى، تصور مليئةً بالجمال والحياة.

تم تصوير الفيلم خلال عام ٢٠١٤, وذلك قبيل الغزو الإسرائيلي على المنطقة. وللمرة الأولى، الأهمية ليست موجهة على العنف، بل تدخل الكاميرا إلى الحياة اليومية: الأولاد يلعبون في الأزقة، الخيول تغسل في مياه البحر المتوسط الدافئة، والرجال يحضرون الفلافل، ويشيدون الاغاني معاً في الديار.

بين الحين والاخر، تتحول لقطات نشاشيبي وصورها، إلى رسوم متحركة، تشبه قصص الأطفال: فالموسيقى وبعض المشاهد تبدو غريبة عن السياق.

في هذا الإطار، تبدو غزة المثبتة في هذه المرشحات المليئة بالعاطفة الواعية، خيالاً مستحيلاً.

تميل أفلام نشاشيبي إلى الانطواء على الذات حيث يظهر التصوير عبر البناء السينمائي، تجميلاً واعداً. بينما في أفلامها الاخرى، تظهر بطء كاميرا نشاشيبي واستقصائها، سحراً في الأنشطة الروتينية.

في الكتريكال غزة، يلحظ قوة أخرى في العمل.

هذه المشاهد مهددة بمأساة ضمنية لهذه المنطقة، والتي ترجع إلى الوراء على أسئلة الغرائبية المربوطة بنظرة نشاشيبي.

طلقة واحدة أخيرة عبر سماء رفح متجهة نحو مصر، تستريح عند المعبر الحدودي. يصاحب هذا المشهد موسيقى بنجامين بريتن (1939)، وهو تكيف أوبرالي لإضاءات آرثر رامبو. كلماته تترجم إلى "أنا وحدي أمسك مفتاح هذا العرض الوحشي." لكن هذا العمل، إن وجد، يعرف زيف هذه المشاعر

One family as an entire community ‘Hreash House’ shows an extended Palestinian family living a collective existence in a concrete block in Nazareth. It shows a feast and its aftermath during Ramadan.

عائلة واحدة تعكس صورة مجتمع كامل. في "بيت هريش" تعيش عائلة فلسطينية ممتدة حياة جماعية في مربع سكني أسمنتي في الناصرة. يصوّر الفيلم أحداث وليمة إفطار في شهر رمضان، والعواقب التي تتبعها

One slow, hot afternoon in a neighbourhood built to be a utopian suburb for employees of the Palestinian Post Office; now becomes a lawless no-man’s-land between occupied East Jerusalem and Ramallah.

ظهيرة بطيئة وحارّة في حي سكني بُنيّ ليكون ضاحية مثالية لموظفي مكتب البريد الفلسطيني، ولكنه صار الآن أرضًا قاحلة بلا قوانين تحكمها بين القدس الشرقية المحتلة ورام الله

An interview about Electrical Gaza

George Vasey: Could you give a brief context to the commissioning process behind your new film for the Imperial War Museum, Electrical Gaza?

Rosalind Nashashibi: I was asked to propose a new work on the subject of Gaza, so the impulse came from the IWM curators initially – they asked other artists to propose who weren’t connected with Palestine, as far as I know. I had thought I hadn’t been to Gaza but my mother reminded me that we had visited once with the family when I was very small, four or five years old, and she showed me a photograph of us having a picnic on the beach.

GV: When did you shoot the footage?

RN: The filming took place in June 2014 during the run-up to Israel’s latest war on Gaza, ‘operation protective edge’.

GV: Wow, I’m always struck by the abstraction of militaristic language. I understand you have a Palestinian father – do you view the film as, in some way, biographical?

RN: My family is from Jerusalem. I don’t view this film as biographical, but when I work in Palestine I’m always seen in relation to my father’s side of the family, and it helps me to move around and to be trusted there. The names of your parents and grandparents are more important to the Palestinians and the Israelis than your nationality, citizenship or language.

GV: And the title, how does the word ‘electrical’ operate in this context?

RN: The word came from a book I was reading a while back about grief, where the writer described the air around him at the beginning of his grief as being electrical. He meant highly charged, tense, artificial and even exciting, but a million miles away from the rush of happiness and life that fresh air can provide. The implication is that you cannot live permanently in that ‘electrical’ air without becoming damaged and exhausted. That made sense as a description of Gaza.

GV: When I was in the gallery, a young couple came in halfway through a screening and one of them asked the other where the film was shot. They had obviously missed the title of the show, yet large parts of the film do feel curiously placeless. The conditions of Gaza only become apparent at particular moments. In the context of the IWM, the film countered the typically journalistic representation of Gaza. It refused to depict the place and the subjects just as victims, which unfortunately tends to be the norm.

RN: It was important to me to depict what I saw and felt there as accurately as possible – in terms of a mix of how I remembered it and how I understood it when I got back, in reflection. I have tried to depict Gaza as an enchanted place because that is how I experienced it. I understood this a week after returning to the UK when I was watching an animated kids’ movie. I realised that I could present Gaza through the language and eyes of childhood as an enchanted place, because it exists on a different plane of reality to everything that surrounds it, especially to us here in the UK. You cannot enter Gaza without complex dealings with different authority groups. Most of that process is hidden and opaque and the outcome insecure. To enter Gaza through Israel is to pass through a process that takes place in a brand-new-looking military facility where you are controlled and surveilled at every step by Israeli guards that you cannot see or touch. The place itself is deserted. Once entered, it is not clear how easily or when you will be allowed to leave Gaza. And this is all before experiencing the peculiar and wired stasis of Gaza and its layers of social protocol. So to go back to the question of victims – that’s not how I experienced the place or the people. My experience was much more contradictory and layered, of a culture reflecting of and on itself, rather than in relation to the world outside.

GV: It is interesting that you mention the children’s film because throughout Electrical Gaza there are moments when the film is translated into short animations that depict the same scene in the film. Often you insert elements that aren’t there in real life. I wonder whether this technique connects to one of your earlier films, 2005’s Eyeballing, where you collate all these anthropomorphic elements from architecture – a doorbell becomes a smiley face etc. There seem to be two ways of seeing the same scene, first through a form of indexical representation and then also through this other filter of the imagination – a child-like eye.

RN: Yes, the comparison with Eyeballing makes sense because both use strategies to show something that is not visible in reportage or verité style filming alone. They are attempts to dig under the images to see what effect they have, to see the moment of cognition taking place. Here the animation was a way of investing much more time and thought into the scenarios than the moments of film alone can offer. The experience of each moment was, of course, multi-layered, and that is something that cannot be easily portrayed through contemporaneous filming. The time of the film is multi-layered, as is my memory of the events: each time animation is used it relates to a live-action scene that we shot, yet it portrays some of its elements faithfully but enhanced and altered, and, as mentioned earlier, suggests another time/space experience of the same moment.

GV: Yes, in one animated scene a group of soldiers appear who aren’t present in the filmed scene. Also, I was particularly struck by an abstract black dot that starts to grow over one scene, forming a redaction – it is striking because there is a sudden shift in representation.

RN: The two scenes you mention visualise elements that weren’t there at the time of shooting. The militants/soldiers/guards were around us but behind the camera on that street and the circle or hole that grows over the scene is an abstraction, yet both anticipate the violence that was coming and that was always there, under the surface. The black circle can be a rupture in the fabric of the film and in the fabric of the place – it’s a sign of death and destruction to come.

GV: Most of this film revolves around the depiction of men. There are only a couple of scenes where women appear, most prominently about halfway through when a group of women are seen looking after young children. In previous films, such as 2009’s Jack Straw’s Castle, you have similarly focused on masculine identity, why is this?

RN: Gaza has a more traditional Muslim society than the West Bank or Jerusalem. Like any society that is sealed, it is no melting pot, and it isn’t influenced much by the world outside. This means that women are less visible than men in public life. Taking care of foreign media – almost always men – is a job for men in Gaza, and so those around us were men. I felt that the most free people in Gaza were the little boys. They were always out in the street and not yet burdened by the twin responsibilities of family and resistance that weigh on the older boys. The girls weren’t so visible – they were on a shorter leash.

GV: You have explored closed and isolated communities numerous times before, of course. I’m thinking of films such as Bachelor Machines Part 1 from 2007, which depicted life on a cargo ship. What is it that draws you to these situations?

RN: It is always hard to say what draws you to the things that you do, it’s a big question. I think I must be drawn to patterns being revealed or structures exposed. I like to look into things in detail by filming, to see how they are made. Closed communities have to be self- sufficient as best they can, each role needs to be fulfilled from within or the machine doesn’t work – which it never completely does, like the bachelor machine. So on the ship or in Gaza, there is a walled universe in each case where the structure of society and of the institutions is closer to the surface. Nevertheless, many things remain mysterious and opaque.

GV: I was wondering what your relationship was to the people in the film. There is one scene where someone making food seems to offer it to the person behind the camera. It is quite a subtle gesture.

RN: The men and women that you see in the film were all brought together to work with us by the ‘fixer’. They were drivers, translators, the family of the fixer and some who were around us for reasons that weren’t made clear. They became familiar to us and every time we were in public it was noticeable that they walked in front, behind and on either side of us in a kind of formation. This was all unspoken. They were working for us, they were buying us ice creams and falafel but at the same time they were protecting us and keeping us in sight.

GV: I really enjoyed the soundtrack, which seemed to move quite effortlessly between ambient house, electro and, finally, Fanfare, a piece of music by Benjamin Britten taken from Les Illuminations. What do you see as the music’s function in the film?

RN: The musical tracks operate as fictional screens. Usually they come in strong and end abruptly in near silence or against some contrast of non-music, so they don’t transform the film into a passive experience for the viewer or a friction-free cinematic ride. They are there to channel the strong reactions I experienced in these moments and in memory. Footage shot on the streets of Gaza is not enough when the job is to direct the viewers’ attention to an inner experience of place and time. One of the tracks is there to transmit the sheer joy and triumph we felt to have finally entered Gaza after years of trying different tactics, and to be bumping along in a car, actually there in Gaza itself. Everyone was smiling and sharing that moment, even the fixer and the taxi driver. That was the experience of the first moments, the short-lived high when Fatah and Hamas had united and before war seemed inevitable.

GV: Later in the film, Britten’s music is layered over a shift in perspective. The camera switches to a surveillance viewpoint. There is a curious conjunction between the previous topographies – homes, markets and alleyways – and this sudden panoramic, colonialist-like gaze.

RN: There are two panoramas that run into one another where the Britten music starts: one is shot from a tall tower in a media facility in Gaza City, and the other is shot from a rooftop in Rafah, looking over the tunnel area and the border with Egypt, a spot for surveillance and from which we were visible to soldiers watching from the Egyptian side.

GV: The scene reminded me of Eyal Weizman’s writing on the ‘politics of verticality’, the sense that Gaza is controlled through the sky, via surveillance, and the ground, by asserting historical sovereignty through archeology.

RN: This is a moment where the conditions of Gaza are made more explicit through a colonial eye that controls through surveillance, but it is also a sweeping look from the sky that could be an overview of an almost religious sort, an epic view, taking in a whole landscape of history and of destruction. That viewpoint often precedes destruction.

GV: The film is not subtitled, and language is treated as a somatic and musical element, a recurring motif of your film work – the gesture rather than the voice is foregrounded. Do you see your films as a form of portraiture?

RN: I don’t see them as portraits. I’m usually trying to understand something that I don’t have language for yet, by making comparisons or juxtapositions so that I can read the friction that occurs between things/times/situations I encounter. People come and go in these scenarios, work their rhythms, and it is part of the weave of what I am both looking at and constructing. What is said is a small part of what happens, equal to glances and movements. In this kind of investigation, words can stand as they are but translating – supplying text – changes their relative importance and introduces reading into the viewer’s cognitive process.

GV: There is a compelling edit in the film where the scene of a group of young men sitting around singing quickly cuts to a Hamas march. Both scenes represent, in different ways, forms of collectivism. The depiction of institutional power is something you have explored in previous films: the police force appear in a number of your films, for instance. Could you expand on this representation of militarism?

RN: I have been looking into our institutions, how we both internalise and navigate them and they navigate us, since I started making films. Cops/soldiers/guards/militants are powerful archetypes that stand in for the control that comes from without rather than within. The men sat together singing. It was a beautiful and harmonious moment, but they were nationalist and resistance songs – some were moving, others were violent. The songs and the joining of voices in a domestic space were acts of resistance and power-building, but also about the simple joy of connection. When that scene meets the one of the Hamas Youth march, I’m thinking that, though there are political divisions in Gaza, resistance to the occupation is a universal cause, and militancy and hospitality are two pillars of Gazan existence.

GV: At the start and near the end of Electrical Gaza we see a group of people transiting through the Rafah border crossing between Palestine and Egypt. This is where the conditions of Gaza become most apparent.

RN: The film starts and almost finishes with chaotic scenes at the Rafah border crossing. The border had been closed for a long time, and, while we were there, the Egyptians opened the border for three days or so. Only a few thousand Gazans were authorised to leave, those who were sick and needed medical treatment outside or had other such urgent situations. But many more flocked to the border to try to leave.

GV: In relation to the border, I was interested in your depiction of the sea, which appears through the film and is often filmed at a distance. In one scene it appears framed on either side by buildings while children play in the foreground. This seems like an important metaphor for me: the sea is often depicted as a site for escape and travel, but here it becomes constricted.

RN: Gaza is locked, and the sea is a beautiful vista but, in some way, false. It was exciting to be at the sea in Palestine as the West Bank always feels so hemmed in by Israel, by the checkpoints and the separation wall, and by the settlements inside. You are never far from the sea but the coast apart from that of the Gaza Strip was all taken by Israel in 1948. In Gaza, however, Palestine is on the sea all the way down. It was breathtaking to have that expanse to look out on, but try taking a boat out for more than a few kilometers and you will be shot at by the Israeli navy that routinely patrols the limits of its blockade. So these features – the sea and the impenetrable borders – define Gaza’s limits and they are in everything and everyone all the time.

Rosalind Nashashibi interviewed by George Vasey in Art Monthly, November 2015.

جورج فاسي: هل يمكنك شرح عملية التكليف وراء فيلمك الجديد لمتحف الحرب الامبراطوري، "Electrical Gaza" كهرباء غزة؟

روزاليند النشاشيبي: طلب مني اقتراح فكرة او عمل جديد عن موضوع غزة، لذالك، جاء الدافع من أمناء متحف الحرب الإمبراطوري IWM في البداية- طلبوا من فنانين اخرين ان يعملوا على هذا الموضوع لكنهم لم يكونوا مرتبطين بفلسطين، على حد علمي. ففكرت أني لم اذهب الى غزة لكن ذكرتني امي باننا زرنا غزة مع العائلة لما كنت صغيرة جدا، في الرابعة أو الخامسة من عمري، ثم أظهرت لي صورة لنا ونحن في نزهة على الشاطئ.

متى بداتي بالتصوير؟

بدا التصوير في يونيو ٢٠١٤ خلال اخر حرب شنتها إسرائيل على غزة الذي تسمى“operation protective edge”.

واو، أنا دائمًا مندهش من تجريد اللغة العسكرية. لديك اب فلسطيني- هل ترين هذا الفيلم بطريقة ما، كسيرة ذاتية؟

عائلتي من القدس. انا لا أرى هذا الفيلم كسيرة ذاتية، ولكن عندما عملت في فلسطين، يُنظر إلي دائمًا على صلة لجانب ابي من العائلة، و ساعدني ذالك على التنقل و التواجد هناك. أسماء والديك وأجدادك أكثر اهمية للفلسطينيين والإسرائيليين من جنسيتك، او لغتك.

والعنوان، كيف تعمل كلمة "كهرباء" في هذا السياق؟

جاءت الكلمة من كتاب كنت أقرأه منذ فترة عن الحزن، حيث وصف الكاتب الجو المحيط به في البداية

من حزنه على أنه كهربائي. كان يقصد مشحونًا للغاية ومتوترًا، مصطنع ومثير، ولكن على بعد مليون ميل من اندفاع السعادة والحياة التي يمكن أن يوفرها الهواء النقي. المقصد هو أنه لا يمكنك العيش بشكل دائم في جو "الكهرباء" دون أن تتضرر وتستنفد. وهذا هو وصف غزة.

عندما كنت في المعرض، جاء زوجان شابان في نصف العرض وسأل أحدهما الاخر عن مكان تصوير الفيلم. من الواضح انهم لم يقرأوا عنوان الفيلم، لكن اجزاء كبيرة من الفيلم توحي الى عدم وجود موقع ثابت. تتوضح مواصفات غزة فقط في لقطات معينة. في سياق متحف الحرب الامبراطوري IWM، الفيلم عارض التمثيل الصحفي النموذجي لغزة ورفض تصوير المكان والناس على أنهم ضحايا فقط ولسوء الحظ هاذي هي الصورة المتعارف عليها من قبل الصحفيين.

كان من المهم بالنسبة لي تصوير ما رأيته وشعرت به هناك بدقة- من ناحية كيف تذكرته وكيف فهمته لما رجعت. حاولت ان اصور غزة كالمكان الساحر لأن هذه كانت تجربتي في غزة. فهمت هذا بعد أسبوع من عودتي إلى